Outwardly, the 1924 Hauser is smaller than modern Spanish instruments and is a typical guitar in German tradition whose very exaggerated hour glass figure seems to derive from the work of Johann Anton Stauffer (1805 –1843). The back and sides are made from European maple, but the guitar is much shallower in depth than is typical of Spanish classical or even flamenco guitars. Unlike Spanish guitars which increase about 10mm from the neck to the end in depth, the 1924 Hauser, like many German instruments of the period, increases in depth from the neck to the waist, and then becomes shallower again. Structurally, this profile is designed to give an arch the back lengthwise. It is also domed slightly, rising about 2mm from the edge to the center. The back made from two pieces is joined without center strip, and glued without bindings to the sides. The sides are glued to the neck and end blocks, and not fitted as into the neck assembly as is the case with the Spanish foot. A wedge of ebony with a peg for a guitar strap adorns the join of the side over the end block.

The top is also slightly domed, lifting perhaps 2mm toward the center both in length and width, coming with the pivotal point centered along a line passing under the saddle. There are three thin bands of purflings around the edges alternating white, black, and white in color. The rosette which is only 8mm wide uses two bands of the thin edge pattern separated by three wider black bands. The top made from two matched pieces of German spruce, which increase from about 15 grains per inch at the edge to about 25 in the center.

The German spruce used in the top is probably from the supply of wood Hermann discovered in the early 1920s while walking on the outskirts of Garmisch. According to an interview with Hermann Hauser II:

"Hauser passed the home of a zimmerman, a rough carpenter, who specialized in hewing logs for the beams and rafters of farm houses. This fellow was in the middle of the yard in the midst of a great supply of logs and was busy with a broad ax, squaring them. Hauser took a close look and rushed into the yard yelling, "You are a gangster!”

When the astonished carpenter recovered from his surprise, Hauser explained to him that he was chopping on the finest grade of mountain spruce, a wood suitable for the sounding boards of stringed instruments. A deal was consummated on a more friendly basis and Hauser bought the entire supply of wood. This was cut to more convenient shapes and send to Hauser's shop in Munch (Herttig 1983:11-12).

Apparently, Hauser used this wood for the rest of his life, and his son was using the last of this magnificent wood when Herttig interviewed him in 1983. If this is the wood that Hauser used in this 1924 instrument, it may help to partly explain this guitar remarkable purity of tone.

One of the features that stands out is the asymmetrical strutting Hauser used in the top. The purpose of this design seems to be to stiffen the treble side of the top and strengthen the treble response. Although Santos Hernandez also used a sloping horizontal bar for this purpose, Hauser had developed this idea independently, and, in fact, patented this design in 1920. The top has five scalloped bars. Two traverse bars between the neck block and sound hole. One traverse bar just beneath the sound hole. One diagonal bar running from just below the waist on the base side to the mid-lower bout on the treble side. And one traverse bar just beneath the bridge. There is a bridge plate through which the bridge pins. There is also a similar sized plate between the traverse bracing about the sound hole, and a somewhat large plate that follows the contours of the neck block above the uppermost brace. There is some thought that the plate beneath the bridge, in addition to securing the bridge pins may encourage a more even quality of sound across all the strings.

The bracing on the back consists of three traverse bars: one in the middle of the upper bout; one just below the waist; and, one in the middle of the lower bout. The center seam joining the two halves of the back is reinforced by a strip of wood running its length.

The linings used to glue the top and back to the sides of guitar are made from plain continuous strips, and notched to accommodate the traverse bars.

The end block is of rounded pine, and is drilled for a strap peg.

The neck has a number of distinctive features. It is appears to be Honduran mahogany that has been lacquered black, with an ice cream cone type heal. The neck fits into a dove-tail joint, but is fastened to the body by a bolt which is set into the heal and goes through a threaded nut set into the neck block emerging on the other side. The dove-tail joint is cleverly made by constructing the neck block of several pieces. The inner member appears was formed by cutting V shaped wedge out. This pine wedge was glued to the neck assemble and so fit perfectly into the V shaped slot. The pieces with the V slot were then backed by another piece of wood, one side of which was then rounded.

The headstock is distinctively different from the guitars from 1925 on which paid homage to Torres and Manuel Ramirez. Rather, it has a crest like a flattened m with an oval hole through with a guitar strap was probably attached. Hauser uses a v-joint to attach the head to neck, a feature that he carried over into his Spanish-style guitars, but one which is not characteristic of Spanish instruments.

The ebony fingerboard has twenty frets, including a zero fret just in front of the nut which seems to function somewhat like the saddle and contribute to the guitar's volume, sustain, and evenness of tone. This is also a feature seen in some of his later work. There are position markers at the 5th, 7th, 9th, 12th and 17th frets. Like on a violin, the Hauser's fingerboard floats above the body of the guitar.

The tuning machines appear to be made of nickel, perhaps by Landstorfer, with ivory grips.

Hauser seems to have experimented with a number of bridge types, including adjustable bridges with metal tailpiece assemblies that fastened to the bottom of the guitar. On this guitar, he used a simple elegant pin bridge with what might be described as a pointed mustache.

The Hauser Riddle

1924 Hermann Hauser played by Randall Avers

This guitar presents a puzzle. It has tonal characteristics concentrated trebles of remarkable purity, great separation, balance and evenness of tone, qualities abundant in his later work, yet the design and construction of this instrument could not be more different. Although the 1924 Hauser has a lovely voice, there are some differences in the sound and tone. The basses are not as quite as resonant, nor does it have quite the volume of those he built in Spanish tradition. While one suspects that the wood Hauser used might hold part of the answer to this riddle--at least in terms of the purity of sound-- but I suspect is real answer is more profound. As José Romanillos notes (Courtnall 1993:125-126), rather than fan bracing, European makers used several traverse bars across the soundboard. As a result, their soundboards are tighter and higher pitched than are guitars that use fan struts. While European guitars may have nice trebles, the basses are restricted, and lack vibrancy. While Romanillos goes on to say that the Spanish guitar is more lightly built, and is designed to get the soundboard and the air cavity to vibrate at their optimum, the 1924 Hauser, too, is a remarkably light guitar, and the whole instrument vibrates when played. Features like zero fret which seems to be designed to transfer energy back to the body suggest that Hauser was already aware of many of the same principles that Spanish makers were using, but approached them in a different manner. We certainly see this in his patent of the diagonal bar. While Romanillos holds that Hauser had to forget the German tradition in order to produce the kind of sound Segovia was looking for, what this 1924 Hauser suggests is what had to do was to translate what he knew about guitar making into the Spanish tradition-- and what took him so much time and effort to figure out was the methods these great Spanish luthiers used to control the same sorts of variables that he controlled using German methods. This guitar suggest that Hauser was not a mere copyist, but a true innovator who brought considerable knowledge to the Spanish tradition and enriched it.

References

Courtnall, Roy. Making Master Guitars. London: Robert Hale, 1993.

Hutting, H.E. "Remembering Hermann Hauser II." The Guild of American Luthiers Quarterly. Vol. 11, No. 3.

Morrish, John. The Classical Guitar: A Complete History. London: Outline Press Ltd.

Segovia, Andres. "In Memoriam, Hermann Hauser." Guitar Review, Vol. 16, 1954.

Urlik, Sheldon. A collection of Fine Spanish Guitars from Torres to the Present. Commerce, CA: Sunny Knoll Publishing Company, 1997.

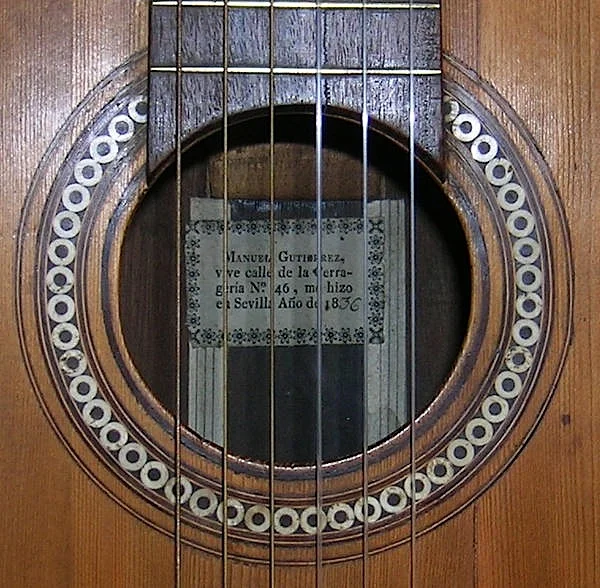

![ José López Beltrán / unico discipulo / de / Don Antonio Torres / Teatro Apolo / Almería Año 18 [94] penned in.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/532cbb0ae4b010786b5af813/1437442320007-2FFC618O76524Z2XKSCN/1894LopezBeltran-rz1.jpg)